Editor’s Note: A guest contribution from K. Ferr to The Prepper Journal.

So you’ve done your homework and put together your last-ditch kit – you’re prepared to make a 72 hour foot hike to your bug out location. You’re prepared to fell trees, repel armed intruders and treat major arterial bleeding.

But are you prepared to actually hike for three days?

As it turns out, there is an entire group of people who do just that, frequently and for fun. These people are called hikers, and they have some concerns about that beastly kit you’re planning to schlep on your back in an emergency. How many of these apply to you?

#1: You’re Relying on a Mylar Sheet as Your Primary Shelter

Before you rely on that flimsy piece of plastic, make sure that you take it out of the package and experiment with it. If you are hiking for three days, that means two overnights – will your Mylar sheet survive being pitched and taken down twice? Mylar blankets rip easily – and once a side has even a slight tear, a light breeze will quickly split the sheet in two.

Mylar blankets are best used as a heat reflecting roof to a more robust shelter, but you almost certainly don’t have time to be whipping up a cozy little lean-to from dead fall if you are going to make good time on your hike. Even if you manage to construct such a shelter, you would need to rely on a fire to warm it (see Problem #6 below).

That’s all right, you say – I’ll just roll up in my space blankie and drift right off.

If you do, I hope you have a lot of layers on. Mylar blankets don’t breathe – at all. Even if you’re cowboy camping under a clear sky, you will wake up soaked by your own sweat, with that tiny plastic sheet clinging to your clammy body (if you’ve managed to stay inside it through all of your tossing and turning).

If you absolutely have to rely on a Mylar blanket, get a good one that is laminated to a sturdier tarpaulin material and has proper tie-outs on the corners. Or do yourself a favor – replace yours with a silnylon poncho that will keep you dry and survive the length of your hike for only a few grams more.

#2: You Have Poop On Your Hands

If you are going on a three day hike, you can expect to need to move your bowels at least three times, eat fifteen to twenty-four times, urinate often and handle your water bottle frequently for refilling.

What happens between these activities is important!

Gastrointestinal illnesses are the most common reason for emergency evacuations in national parks – not gunshot wounds. If you forget the soap or hand sanitizer, you are going to find yourself pooping way more than three times. And if you forgot the wet wipes, I’m willing to bet you were planning to use leaves for toilet paper, too. There are green leaves where and when you’re going, right? No? How do you feel about pine cones on your nether bits?

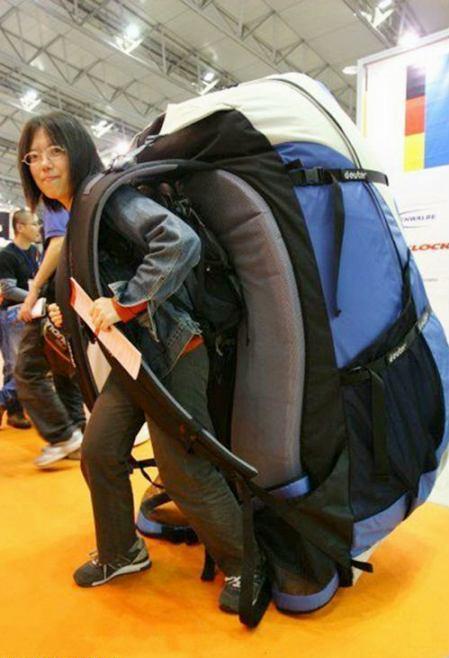

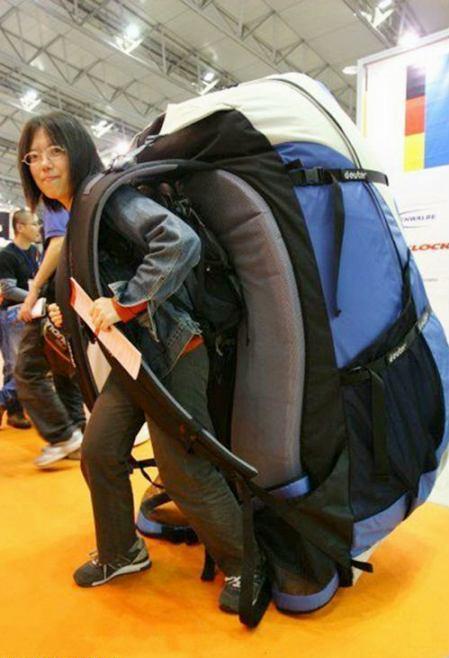

#3: A Boulder Is Dangling From Your Shoulders

It doesn’t matter how many straps your bag has, from a load bearing perspective, the only thing that really matters is the straps that attach it to you.

Messenger bags are terrible at distributing weight, no matter how padded the straps are. So you did the smart thing and got yourself a sweet tacticool assault pack that would outlast your grand kids and fend off a charging rhinoceros. It’s 20,000D ripstop kevlar-infused unicorn hair, and nothing is taking that bad boy down.

Granted, the pack alone weighs eight pounds. And then there’s the forty pounds of tools and backup tools that you’ve squeezed into it. So, forty eight pounds, no problem! That’s like a kindergartner. You lift kindergartners all the time with your bare hands, let alone two (count ’em, two!) mesh-backed foam-padded shoulder straps!

Give it four hours, and you are going to be in tears. The human body is just not designed to carry heavy loads suspended from its (ripped, chiseled, god-like Alpha prepper) shoulders. For one thing, that much weight will constrict blood flow to the muscles that are actually bracing the weight, which will fatigue you more quickly. For another, it requires you to bend over to balance the load, compressing your lungs and making it impossible to breathe deeply. And lastly – it hurts. It hurts when you’re doing it, and it hurts a lot more the next morning.

For any load over 10 pounds that you are going to carry long distance, you need a backpack with a padded hip belt, sternum strap, and load lifters on the shoulder straps!

#4: You Have to Stop. All. The. Time.

3:00 Finally off the highway and on to the planned bug out route.

3:10 Getting hungry, stop and take off pack for food, set pack down in the wet leaves.

3:15 Back on the trail.

3:42 Snack leading to thirst, stop and take off pack for water bottle, juggle awkwardly while removing lid with one hand.

3:44 Back on the trail.

3:53 $%&@! Nose is running. Stop and take off pack…

Think of the front half of your pack system as your car’s driver seat. You want certain things in reach so that you don’t have to pull over every time you need something if you’re going to get anywhere fast. Think water bottle holsters, waist belt pockets and add on pouches to make sure you can keep on truckin’ for at least an hour and a half between short rests (while, yes, looking like a complete dork).

#5: Your Bag is Jammed to Bursting

You’ve packed that bag as tightly as you possibly can, squeezing every last bit of space to fit that backup Laplander saw and four kinds of spare batteries for all of your flashlights. You stand back, hands on hips, and give a sigh of great satisfaction over your elite gear-tetris powers.

Fast forward to the end of the world. You’re striding confidently through the brush, making good time. You spot a squirrel – to hell with keeping up a pace, it’s time to bust out that slingshot! You unzip your pack, and its contents explode over the forest floor. Which bag was it in? Right, it was inside your cooking pot. Finally, you get to your feet and peg the little rodent. He drops from the tree and you carry your small fluffy kill back to your bag in triumph.

You wrestle your slingshot back into your cooking pot and manage to get everything back into the bag (sitting on it helps the zipper close). Time to head on.

Wait. Where are you putting Fluffy?

Wait. Where are you putting Fluffy?

What about that tinder over there? You’d rather not have to use up all your Wetfire, not if there’s birch bark just lying around. And those rose hips are edible too. Should probably fill up your spare water bottle, while there’s a stream just down the hill. Except that your spare water bottle is crammed full of your first aid implements, you know, to save space and keep them dry.

If you’re planning on foraging on your trip, don’t forget to bring extra carrying capacity, ideally something that you can reach while you’re gathering without having to take your pack off (see Problem #4!).

#6: You’re Relying on a Fire to Stay Warm Overnight

Fire is an excellent tool to have available in an emergency, and it’s very light to carry – just the weight of your fire starting method (and backup method, and backup backup method, and rockin’ $60 thermoblast sure fire tinder…)

But fire is not the solution to every survival problem.

Firstly, fire is dangerous. A fire large enough to keep you warm broadcasts your location, day and night, to anyone within sight of it or its smoke. You also need to be able to keep an eye on it, especially if you’re burning it in a hastily dug hearth (you do make a proper hearth, right? Right down to the mineral soil? With the roots cut out?). And if you’re burning it anywhere that’s relatively safe to leave it unattended, odds are, there’s no readily available fuel, which brings us to our next problem.

Fire is a good caloric multiplier – you spend time and calories, and in exchange you gain calories that you would other need to expend keeping yourself warm, from a source that you couldn’t otherwise eat (wood). The problem with this equation is that you need excess time and excess calories at the front end to invest in carrying your heavy tools to your site and then chopping and hauling all of that wood. How much wood? The general rule of thumb is one mid-sized pickup truck bed of wood per night. Yikes!

Now, hikers love to sleep. They love to sleep so much that they have been known to go from walking to sleeping in ten minutes, because they also like covering crazy distances. The technology that makes this rapid deployment sleeping situation possible is the down sleeping bag and self-inflating air mattress, which weigh less in combination than the lumberjack outfit you are planning on heaving out into the bush just for the privilege of working like a dog after a day of hiking. Unroll, unzip, knock off your boots and crawl in for a full night of sleep undisturbed by the need to constantly feed your fire.

#7: You Are Setting A Picnic for Furry Things

Bears are not the only thing that would be delighted to ransack your camp for all of your delicious high calorie munchies – they’re just the biggest. Sure, a raccoon or a particularly ballsy squirrel might not represent quite the same risk to life and limb as a bear, but none of these issues are something you want to be dealing with at two in the morning (when you’re getting up to stoke your fire for the eighth time, see Problem #6).

Hikers are nuts about bear safety. There are books. There are courses. There are $90 bear resistant bags that get purchased and used, even though they’re heavier than some hikers’ entire clothing systems. But the reason for all of this is not that they’re sorely unarmed – it’s that having your food dragged down a hill and scattered everywhere sucks. The first and best defense is to hang your food and garbage (yes, you can’t just burn it, see Problem #8) up a pair of trees with all of the stone-age technology of a rope and bag.

#8: You’re Making Your Bed Smell Delicious

You’ve decided that you need a fire, because you just can’t live without a hot meal for three days. So you’ve roasted your delicious meats on a stick, sizzling juices dripping with a hiss into the campfire. You’ve boiled up warm canteen cups of soup, maybe dripping a little accidentally into the ground near your feet. Afterwards, you clean up as best you can (you didn’t bring anything to clean with, after all), and toss the water in the bushes next to your campsite. Then you yawn, pull on your long johns and curl up in your super shelter.

Short of scent marking your territory with hot dogs, you can’t be doing much more to attract critters to your campsite. As previously discussed, this is definitely something worth avoiding by separating your cooking and eating area from your sleeping area by at least 200 yards. And yes, this means eating away from your Mylar palace – so maybe it’s not worth putting together a one hour campfire cookin’ extravaganza. You can eat Power Bars for a couple of days and live.

#9: Bug Spray Is Your Only Defense Plan

Where there is smoke, there’s fire. Where there is water, there is bugs. Where there is standing water, there are even more bugs.

Unless you are bugging out to the Mohave, you can expect blood sucking and neck chomping insects to make an appearance at your bugout party. But you came prepared! You have this little stick of bug repellent!

Even if you want to slather yourself with a limited supply of harsh chemicals, there’s a good chance it won’t be enough in your area. For one thing, certain repellents only effective against certain insects. What keeps the mosquitoes away won’t necessarily stave off ticks (you need Permethrin for that). For another, even the most effective bug spray wears off rapidly when you are sweating heavily under forty eight pounds of saws and flashlights.

I think we’ve established that hikers have no fear of looking like dorks, and nowhere is this more apparent than when they resort to head nets (and even bug gloves, those are a thing). But, then again, coming down with Lyme disease just as you’re reaching your bugout location really makes you look like a moron. A sweaty, wetly, nearly catatonic moron.

#10: You’re Planning on Running on Empty

Hikers know that food is heavy. It’s a major part of the weight in their packs. But they don’t try to get around it, because they know that a day of hiking burns 3,000 to 5,000 calories.

It isn’t a matter of “toughing it out” – if you don’t eat, you can’t walk, and it doesn’t take long. Forget your plans to fish and set snares – you’re trying to get to your bugout location in three days, right? You don’t have time to go all Les Stroud on the wilderness. Hikers who walk all day know they need to refuel every two hours or so, just to keep moving at a decent pace. And failing to eat enough for two or three days will have you sick to your stomach, dizzy, and much more likely to injure yourself. Your body also needs extra fuel to keep you warm at night – especially if you didn’t plan for a proper shelter.

Rather than betting on your ability to go from three meals plus snacks and minimal activity to no meals and all-day hiking, look into thru-hiker food lists. These people count every ounce, and they are experts at cramming enough calories into their itty bitty, hideously lime green and orange packs.

Follow The Prepper Journal on Facebook!

. How prepared are you for emergencies?

#SurvivalFirestarter #SurvivalBugOutBackpack #PrepperSurvivalPack #SHTFGear #SHTFBag

Wait. Where are you putting Fluffy?

Wait. Where are you putting Fluffy?